African water politics: a blog outline

Water is an invaluable resource to humans. Even though it makes up for 70% of the earth's surface, only 2.5% of it is freshwater meaning suitable drinking and agriculture. Still, not all of that is accessible. Only 31.3% of the freshwater is in the form of ground and surface water. All of this is not to highlight that freshwater is scarce but that, just as with most natural resources, it requires management.

Now, it would be remiss of me if I didn't acknowledge the problematic language of describing the African continent of many a country as one nation right from the start. As the Nigerian author Chimamanda Adichie talks in her TED talk about the danger of a single story, it is important to realise that the story of Africa is not just one. There is no single story of Africa, the place of starving children, Africa, the poor or Africa, the land of exotic animals. There is certainly no Africa, the country. As a reader of these blogs, therefore, it is of importance that one is always aware and mindful of their own narrative of the continent and realises that water scarcity and water insecurities are often transboundary issues and there is no one problem or one solution shared by all 54 African countries.

On that note, it is crucial to point out that freshwater management is a particular issue for many African countries. A third of the population across the continent faces water scarcity and with the increase of climate change driven floods and droughts, substantial investment is needed in developing climate resilient water and sanitation infrastructure.

|

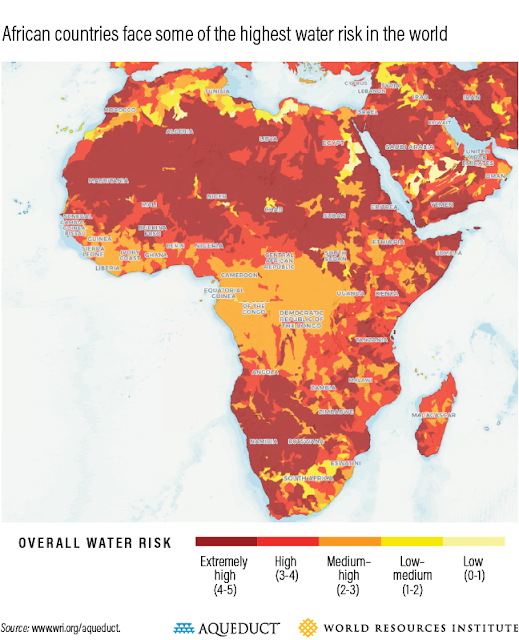

| A map of water risk in Africa which considers drought and

flood vulnerability, water stress and seasonal variability (Mason, Nalamalapu,

& Corfee-Morlot, 2019) |

Personally speaking, even though I'm not a social scientist, my background being more in physical geography, I do have lived experience. Having been born in the East African country of Eritrea and spending the early years of my life up to my early teens there, I have experienced first hand the struggles of having to source clean water. Admittedly I personally never had to travel kilometres or pump wells as we were able to buy bottled water from shops in 10L containers. However, the availability and quality of these was far from ideal and the cost was certainly a prohibiting factor for many households.

Eritrea is not a country where clean water is easily accessible. Although there are seemingly countless water related projects running at any given time- namely the building of dams- in reality, water is hard to come by. People have to wait in lines, often for hours, for a water truck to fill up their containers and that is even if they are lucky enough to live in a city big enough to have water trucks. The rest of the population relies on community water pumps, rivers, jerry cans and donkeys. The main problems for this lack of accessible water are both physical and political, with the country simultaneously being dry and mismanaged (for example, the 2019 closing of big water companies by the government with little explanation).

What I hope to achieve in writing these blogs is mainly to challenge myself to reconcile the physical aspect of water problems with the political side of managing it and providing the reader with an appreciation of the international nature of water cooperation in the context of the river Nile.

You have shown some rudimentary grasp of water and politics issues, but some specific data on water availability backed by literature would have been helful. Also, the use of anectode from Eritrea is good but details that would have provided better understanding of sociocultural, economic and political context are missing.

ReplyDeleteHi Francy

ReplyDeleteIs there any information on why the water companies in Eritrea closed down? Was it a publicly owned system that failed? Are there any movements to allow external investment in the water system within Eritrea? Do you think a change in government would improve the access to water within the area, or do you think it would further destabilise the situation?

Your own experience as an African means this blog is something I'm looking forward to reading.

Cheers

Tim

Hi Tim,

DeleteAs far as I can tell, there was no explanation for why the water companies closed but it is not unusual for the government to act on a whim. I believe the year water companies were shut down was also the same year the government forcibly took over the management of Catholic schools (including my old school) and clinics which were providing especially vital and much better services than government run clinics in rural areas.

In terms of external investment being useful, it would obviously improve many public services, not just the water system in general. But there are no private companies providing public services because the government is opposed to external investment for political reasons but I think a change in government is too radical to tell how it can affect water access. The country has been managed by the same government over the past 31 years and so the uncertainty is too big to say what might happen to water access if management changed. It could be better or it could get much worse.