Africa’s longest geopolitical conflict- a look at the historical context of the hydro politics of Egypt and Ethiopia and colonial agreements

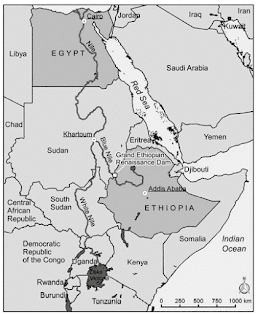

The river Nile is the longest river in the world with an estimated length >6800km.

It has two main tributaries, the White Nile, which originates in southern

Rwanda and the Blue Nile, which originates in Lake Tana, Ethiopia before they

merge in Khartoum and flow towards Egypt and drain into

the Mediterranean Sea. While eight countries contribute to the While Nile, the main contributors of the Blue Nile are Ethiopia (multiple

tributaries generating about 85% of the flow that reaches Aswan, Egypt) and

Eritrea, limited to the Setit tributary. The largest downstream countries are

Sudan and Egypt.

|

Map of the Nile basin (Nasr & Neef, 2016) |

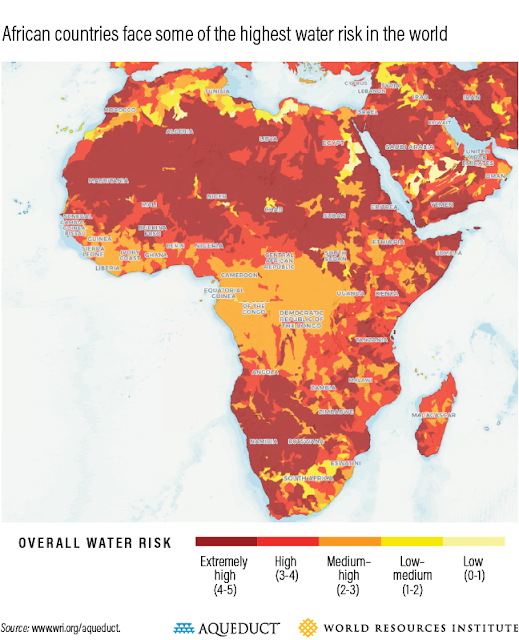

The management of the Nile has been a major source of transboundary contention between Egypt and Ethiopia for centuries. At the heart of it lies the fundamental differences between the interests of a downstream and an upstream nation. Egypt, as a desert country, has always relied on the river for its freshwater supply whereas Ethiopia is only recently starting to exploit the resource for its development. However, Ethiopia’s, the most significant upstream country in the Nile, challenge to Egypt’s hegemony is seen as a threat by the latter.

One of the earliest examples of the conflict between the two nations comes from the 12th century when Amda Syon, the Ethiopian Emperor, threatened to divert the river flow if Coptic Christians continued to be persecuted by Egypt. In more modern times, under the colonial rule of Britain, several agreements regarding the use and management of Nile water were signed amongst parties involved. The earliest of these was the 1891 agreement between Britain and Italy, without much involvement from any of the riparian states. According to the agreement, the Italian government, which was in control of the Tekkeze river in Ethiopia (then called Atbara River), made a commitment not to carry out projects that would significantly change the flow of the river.

The second treaty that came was the 1902 Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty which, as well as demarcating regional borders, allowed Britain, under article III, to secure the uninterrupted flow of water from Lake Tana and the Blue Nile in Ethiopia. However, due to differences in the wording of the agreement between the Amharic and English versions, it was never ratified by Ethiopia. In the next two decades, two more treaties were signed; one in 1906 between Britain, Italy and France and the second in 1925 between Britain and Italy. While the latter of the two had a similar language to the 1891 treaty, the earlier rejected Ethiopia’s full sovereignty over its portion of the river. This was unsurprisingly not accepted by Ethiopia with its leader, Emperor Menelik, describing it as a sinister attempt against the sovereignty of Ethiopia. The next significant treaty was the Nile Agreement of 1929 between Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and Egypt which made provisions for Egypt and Sudan to have access to 48 billion and 4 billion cubic metres of water, respectively, out of an estimated total of 84 billion cubic metres. Ethiopia was never consulted in this treaty. By 1959 the Nile Waters Agreement was signed by the now independent states of Sudan and Egypt which provided the legal framework for the management of the river with Egypt given the right to use 75% of the flow and Sudan 25%. Again, Ethiopia and other up-stream countries were not given a say.

In the next blog, I will explore how the power dynamic between the two countries regarding the use of the river began to change and why.

Comments

Post a Comment