Water war

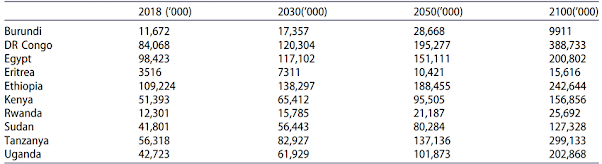

The rapid population increase of North-eastern Africa (projected

to double by 2050 compared to 2014) coupled with climate change and food

insecurity will inevitably put increasing amounts of pressure on Nile water. Former

Secretary-General of the United Nations, Boutros Boutros Ghali once said that

the next conflict in the region would not be because of politics but because of the Nile.

|

A table showing total population by country, 2018, 2030, 2050 and 2100 (medium variant, Turhan, 2020) |

The river, as well as being a vital

natural resource, is also a part of the identity of many Egyptians and Ethiopians

alike. Discussions framed around the resolution of such transboundary conflicts

as the one between Egypt and Ethiopia tend to focus on physical securities such

as the storage capacity of the dam and its general operations. However, the ontological security angle is often overlooked. Ontological

security, as described by Jennifer Mitzen is “the need to experience oneself as

a whole, continuous person [or state] in time – as being rather than constantly

changing – in order to realize a sense of agency”. Prolonged military

confrontations and actions of leaders cannot be fully understood just by considering physical security.

Insofar as Egypt and Ethiopia then continue to have opposing ontological

securities around the Nile, conflict resolution based on established transboundary

principles and norms will be difficult. While Ethiopia looks to build a

collective state identity around the Nile and GERD, Egypt sees this as somewhat

of an existential threat.

Indeed ontological security can be deployed to understand the behaviour of the extremes on both sides. In Egypt, there have been violent demonstrations demanding their country stop the GERD. Successive governments have adopted various hegemonic-compliance themes, namely God-given rights, national security and nationalist austerity, and bread rights. Suggestions by politicians to the then Prime Minister of Egypt, Mohamed Morsi, included sabotaging the dam building through a direct military intervention or by funding armed rebel groups. But, despite the rhetoric on both sides, a war between the two nations over the GERD or the river in general, is unlikely perhaps because of Ethiopia’s status as a rising regional power or Egypt’s financial troubles. However, given the Horn of Africa is not a region often deterred from wars due to poverty, the absence of confrontation cannot be solely justified by Egypt’s economic situation. Ethiopia’s emergence as a regional power can also only explain how Egypt’s monopoly came to be challenged, not why there hasn’t been a war.

It would be helpful to then look at what would be the incentives and drawbacks to a war over water use. Presumably, such a war would be initiated by a downstream country attacking a project like the GERD in an upstream country, but this would lead to the flooding of regions in the downstream nation. Furthermore, the upstream country could also pollute the river as retribution (water terrorism). Based on this, it seems like the costs far outweigh any potential benefits of a military aggression. Ethiopia for its part, as I mentioned in last week’s blog, has adopted a policy of equitable use rather than total sovereignty as the latter would most likely lead to Egypt intervening with every method possible given how much it depends on the Nile. And so, even though an attack from Egypt seems unlikely, it is only that way because Ethiopia has adopted a less extreme principle. Therefore, the mutual destruction nature of a potential war acts as a deterrent for both countries.

Indeed ontological security can be deployed to understand the behaviour of the extremes on both sides. In Egypt, there have been violent demonstrations demanding their country stop the GERD. Successive governments have adopted various hegemonic-compliance themes, namely God-given rights, national security and nationalist austerity, and bread rights. Suggestions by politicians to the then Prime Minister of Egypt, Mohamed Morsi, included sabotaging the dam building through a direct military intervention or by funding armed rebel groups. But, despite the rhetoric on both sides, a war between the two nations over the GERD or the river in general, is unlikely perhaps because of Ethiopia’s status as a rising regional power or Egypt’s financial troubles. However, given the Horn of Africa is not a region often deterred from wars due to poverty, the absence of confrontation cannot be solely justified by Egypt’s economic situation. Ethiopia’s emergence as a regional power can also only explain how Egypt’s monopoly came to be challenged, not why there hasn’t been a war.

It would be helpful to then look at what would be the incentives and drawbacks to a war over water use. Presumably, such a war would be initiated by a downstream country attacking a project like the GERD in an upstream country, but this would lead to the flooding of regions in the downstream nation. Furthermore, the upstream country could also pollute the river as retribution (water terrorism). Based on this, it seems like the costs far outweigh any potential benefits of a military aggression. Ethiopia for its part, as I mentioned in last week’s blog, has adopted a policy of equitable use rather than total sovereignty as the latter would most likely lead to Egypt intervening with every method possible given how much it depends on the Nile. And so, even though an attack from Egypt seems unlikely, it is only that way because Ethiopia has adopted a less extreme principle. Therefore, the mutual destruction nature of a potential war acts as a deterrent for both countries.

In the upcoming blog, I will briefly discuss what are the potential benefits of the GERD to Egypt.

Comments

Post a Comment